We flew in from New York to Santiago, Chile two days ago. We spent about five hours walking around Santiago today.

One of the things we immediately noticed here, as we have everywhere we travel in the world, is the difference between the weight of people here and those back in the U.S.

The people here look like Americans from old family photos and faded newspaper clippings from the 1950s, 60s and early 70s.

When we walked the streets of New York, and as we traveled around the U.S. over the last two years, we saw firsthand how Americans, and the socially accepted body image of “normal” Americans, has changed dramatically since we grew up. Americans are now plus size and the rest of the world is still wearing 30×32 Levis.

So what happened? How did America go from lean and mean to weak and waddling?

Since it happened on a society-wide scale (no puns intended), in my view, it must be a society-wide cause.

I’m not a scientist, but it doesn’t seem like this is a rocket science level question. When you start looking for society-wide factors that strongly correlate over the same time frame, it only takes a little bit of research to turn up the leading suspect: High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS).

Starting about 1970 the U.S. food industry enthusiastically adopted HFCS. They liked it so much they basically stopped using real sugar in Americans’ processed food and drinks. For instance, HFCS is now the only sweetener used in non-diet soft drinks, e.g. sport drinks, fruit juices, cola, pop, and soda. It is also widely used in other food products such as soups, condiments (ketchup), deserts, crackers, cereals, etc.

HFCS is cheaper than sugar and it tastes much sweeter. That was a powerful combination for the food and beverage industry and the American consumer. So powerful, in fact, it proved irresistible.

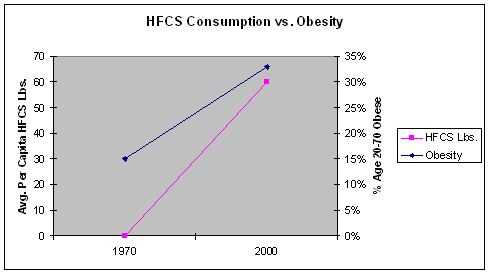

Consequently, average annual per-capita consumption of HFCS in the U.S. went from zero in 1970 to over 60 pounds (27.22 kilos) today. That means that every single American you know consumes an average of over 60 pounds (27.22 kilos) of HFCS every year. If you consume less, then someone else is consuming more. You probably noticed them at the mall the last time you went there.

The HFCS Americans consumed was primarily delivered via soft drinks, fruit drinks and other non diet drink delivery platforms. For instance, in 1988 Taco Bell introduced unlimited soda refills and 7-Eleven the 64 ounce “Double Gulp.” Consumption volume of drinks and other processed foods skyrocketed as a consequence of these and similar “super-size” market offerings (see figure one).

Figure One

Source: USDA-ERS

During the same period, obesity in America skyrocketed (see figure two).

Source: CDC

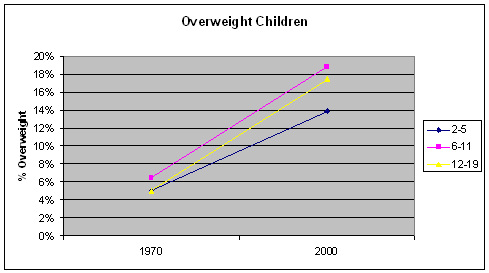

And the effects were not limited to the adult population (see figure three).

Source: CDC

Here’s what this march to national obesity looked like by state (see figure four).

Figure Four

Source: CDC

How bad is it? How much have our perceptions and perspectives changed? Earlier this year it was hailed as a triumph when adult women’s obesity rate stabilized at 33.2%. America actually celebrated at the news that one in three of its women were obese. Less encouraging was the news that adult American men continue to chase their women. The men are at 31.1% and climbing. The overall adult obesity rate in America doubled between 1980 and 2002.

The news is even more depressing with children. 17.1% of 2 to 19 year olds were obese in 2004, with 18.8% of 6 to 11 year olds leading the way to health oblivion.

How did this happen to our children? According to Safak Guven, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, “The increase in juvenile obesity is caused by a variety of factors, including time spent watching television and playing video games, high-calorie foods such as soda that have little or no nutrition, and a family environment where overeating and a lack of exercise are the norm.”

It is not just children who are combining high-calorie foods with little to no exercise. The health effects of this three decade decline have been disastrous, and include an explosion in Type 2 diabetes among adults, and even more worrisome, this adult disease is now common among young children.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), overweight and obese individuals are at increased risk for many diseases and health conditions, including the following:

-

Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Osteoarthritis (a degeneration of cartilage and its underlying bone within a joint)

- Dyslipidemia (for example, high total cholesterol or high levels of triglycerides)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Sleep apnea and respiratory problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, and colon)

Not overweight and don’t really care? Don’t see any impact on your personal life? Consider the economic impact (see Table One).

Table One: Aggregate Medical Spending, in Billions of Dollars, Attributable to Overweight and Obesity, by Insurance Status and Data Source, 1996–1998

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$7.1 |

$12.8 |

$3.8 |

$6.9 |

|

|

$19.8 |

$28.1 |

$9.5 |

$16.1 |

|

|

$3.7 |

$14.1 |

$2.7 |

$10.7 |

|

|

$20.9 |

$23.5 |

$10.8 |

$13.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note:

Calculations based on data from the 1998 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey merged with the 1996 and 1997 National Health Interview Surveys, and health care expenditures data from National Health Accounts (NHA). MEPS estimates do not include spending for institutionalized populations, including nursing home residents.Source: Finkelstein, Fiebelkorn, and Wang, 2003

As shown in Table 1, in 1998 aggregate adult medical expenditures attributable to overweight and obesity is estimated to be $51.5 billion using MEPS data and $78.5 billion using 1998 National Health Accounts (NHA) data. For obesity alone, the estimated costs are $26.8 billion and $47.5 billion, respectively. The inclusion of nursing home expenditures in the NHA estimates causes most of the difference between the MEPS and NHA results.

Since it is now nearly 2008 and the obesity rates have continued to climb since 1998 when this data was collected, our annual national costs are now significantly higher than the $78.5 billion reflected in Table One. And these are, for the most part, recurring costs driven by the chronic disease states spawned by excess weight and obesity. These costs will not be going away anytime soon.

This is everyone’s problem, whether you are overweight or not.

We are killing ourselves as a nation, and those that don’t die in the short term will be long-term burdens on the society due to the range of chronic diseases that are hallmarks of this condition.

As I mentioned, I am not a rocket scientist. Or even a scientist. But I don’t think it takes one to see what has happened, and continues to happen, regarding this issue.

Let’s get our heads out of the sand.

Do you consume HFCS? Do your children?

Can you identify the foods and drinks in your diet that contain HFCS?

What are we doing to ourselves? What are we doing to our children?

We are slowly but surely killing ourselves, our children and our nation.

We don’t see that slow but sure death happening to the people and the children walking the sidewalks here in Santiago or anywhere else we’ve been in the world.

Obesity, a lifetime riddled with chronic disease and premature death are not a requirement of modern life here and they don’t need to be in America.

Selected excerpts from related scientific research:

The consumption of HFCS increased > 1000% between 1970 and 1990, far exceeding the changes in intake of any other food or food group. HFCS now represents > 40% of caloric sweeteners added to foods and beverages and is the sole caloric sweetener in soft drinks in the United States. Our most conservative estimate of the consumption of HFCS indicates a daily average of 132 kcal for all Americans aged > or = 2 y, and the top 20% of consumers of caloric sweeteners ingest 316 kcal from HFCS. The increased use of HFCS in the United States mirrors the rapid increase in obesity.

The digestion, absorption, and metabolism of fructose differ from those of glucose. Hepatic metabolism of fructose favors de novo lipogenesis. In addition, unlike glucose, fructose does not stimulate insulin secretion or enhance leptin production. Because insulin and leptin act as key afferent signals in the regulation of food intake and body weight, this suggests that dietary fructose may contribute to increased energy intake and weight gain. Furthermore, calorically sweetened beverages may enhance caloric overconsumption. Thus, the increase in consumption of HFCS has a temporal relation to the epidemic of obesity, and the overconsumption of HFCS in calorically sweetened beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity.

Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge

Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), particularly carbonated soft drinks, may be a key contributor to the epidemic of overweight and obesity, by virtue of these beverages’ high added sugar content, low satiety, and incomplete compensation for total energy. Whether an association exists between SSB intake and weight gain is unclear.

We searched English-language MEDLINE publications from 1966 through May 2005 for cross-sectional, prospective cohort, and experimental studies of the relation between SSBs and the risk of weight gain (ie, overweight, obesity, or both). Thirty publications (15 cross-sectional, 10 prospective, and 5 experimental) were selected on the basis of relevance and quality of design and methods.

Findings from large cross-sectional studies, in conjunction with those from well-powered prospective cohort studies with long periods of follow-up, show a positive association between greater intakes of SSBs and weight gain and obesity in both children and adults. Findings from short-term feeding trials in adults also support an induction of positive energy balance and weight gain by intake of sugar-sweetened sodas, but these trials are few. A school-based intervention found significantly less soft-drink consumption and prevalence of obese and overweight children in the intervention group than in control subjects after 12 mo, and a recent 25-week randomized controlled trial in adolescents found further evidence linking SSB intake to body weight.

The weight of epidemiologic and experimental evidence indicates that a greater consumption of SSBs is associated with weight gain and obesity. Although more research is needed, sufficient evidence exists for public health strategies to discourage consumption of sugary drinks as part of a healthy lifestyle.

Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB.

Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health

Note: Emphasis added is my own.

Sources:

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)

- National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS)

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- Food Science Nutrition

- Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health

- Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University

- Department of Pharmacology, German Institute of Human Nutrition

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

The effect of HFCS is well-documented and — at least until his wife started actively running for President — was the focus of a speaking tour by former President Bill Clinton.

Here at our house we have grown ever more vigilant, substituting natural maple syrup for “pancake syrup” (which contains both “corn syrup” and high fructose corn syrup” — as well as sugar!), eliminating sodas, and the like.

When our then-12-year-old son Lex got tired of being fat, he cut out sodas. It was like a miracle cure. You’ve seen him recently: He looks like the “after” photo in a Charles Atlas ad.

Finally, I always remark upon this: When I was 12, I got little or no exercise, spending lots of time by myself reading, and guzzled “free” sodas like Mountain Dew filched from my father’s automatic car wash business on a regular and copious basis. I also ate pretty much whatever I wanted (and it wasn’t a lot of vegetables). I never gained an ounce. Now most kids I see are struggling with a weight problem. What has changed? All the crap we have loaded our food with, most notoriously high fructose corn syrup.

The topic of childhood obesity is of great importance throughout the world and considered a global epidemic as of recent years. Of all countries to date that have reported on the prevalence of obesity, paediatric obesity continues to increase showing rapid environmental and lifestyle changes (Reilly, 2006). Reilly continues by reporting that in the developed world prevalence of paediatric obesity is similar between boys and girls and generally more common in adolescents from families of lower socieconomic status. In the developing world the picture is more complex. A higher risk of paediatric obesity is associated with higher socioeconomic status, although the research suggests that as the epidemic progresses in the developing world lower socioeconomic status may become more of a risk factor.

Numerous factors relating to socioeconomic status are reported as contributing to childhood obesity. After a literature review, Hunt (2002) noted that low levels of cognitive stimualtion and income are major contributing factors. Parental weight is also closely connected to the weight of their children. Perhaps partially genetic but lifestyle factors, family structure, and coping with the process of change influence the weight of our children. Formula feeding during infancy, consumption of sugar sweetened drinks, excessive television viewing, and low physical activity have been identified as the four behaviors targeted as the highest priorities for interventions aimed at paediatric obesity (Reilly, 2006).

Besides the costs to society associated with chronic health conditions resulting from obesity is the concern of decreased quality of life for our children. Problems such as low self-esteem and depression may pose life-long hardships that affect all aspects of their lives.

Primary and secondary prevention must occur in the home. Our children are less likely to make healthy eating and activity decisions if we are not making the same decisions ourselves.

Hunt, J. (2002). Influence of the home environment on the development and treatment of childhood obesity. Paediatric Nursing, 14(1), 10. Retrieved May 2, 2007, from ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source database.

Reilly, J. J. (2006). Obesity in childhood and adolescence: evidence based clinical and public health perspectives. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 82, 429-437. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprintform

Brilliant article. I appreciated your use of the graphs especially the changing graph of obesity over time. HFCS has invaded our food supply. Courtesy of the Corn Refiners Assoc., go to http://www.corn.org/NSFC2006.pdf P29-30

list all the foods and products that contain

HFCS. A few surprises even for me: bagels, yogurt, cough syrups. Shapiro, the author of Exposed, a book about the toxic substances we are exposed to in everyday life, made some statements during a NPR interview that are

germane to the HFCS issue. He said that European governments are genuinely interested

in the health of their citizens down the road

because the European governments pay the health care bills. (Europe prohibits the use

of genetically modified foods (GMO) which

safely eliminates HFCS.) In the US our health

care is mostly private, and corporate interests

either through political contribution or

lobbying congress influence our government to

look the other way. Why is that Coke in Europe is made with real sugar and is still served in 6 oz glass bottles and Coke in the US is only

sweetened with HFCS and we guzzle liters.

Golly gee, could it be the HFCS?

Doug, the statistics on obese people in American is not surprising. We all talk about it and I observed it first hand in Dallas Texas during the holiday season as I shopped and did the ‘honey-do’ tasks for my aging mother. I am shocked to see rippling blubber everywhere I go. In the sheltered space of Telluride you just don’t see it. I am sending this link to several friends who observe the overwhelmingly huge people in our country.

Have fun in Valparaiso

Yikes! what to do?

Tom