In the posts Show Me Your Budget and Buying Boxes I addressed the components and priorities of the United States government budget and how we as a nation pay for that budget. What I did not address are the components of that budget that are on rapid growth curves and the implications therein.

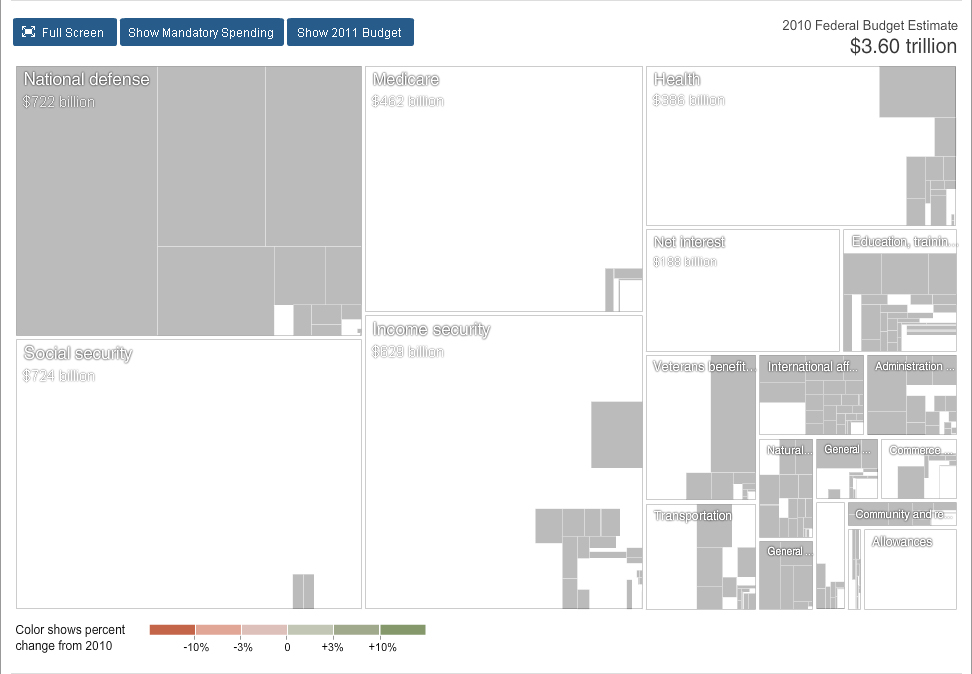

Of the overall United States government budget, very few components are actually under the spending control of congress on an annual basis. The elements of the budget that can be varied year to year are termed discretionary; the elements that cannot be varied by congress are termed mandatory. The following graphic illustrates the areas of the 2010 budget that comprise the discretionary spending components.

(click image for larger size)

2010 Budget Discretionary Spending Components

As you can see, very little of the $3.6 trillion dollar 2010 budget is discretionary. Mandatory items are “hard wired,” under our existing system, they cannot be varied by congress or the president. Most of the “hard wired” nature of mandatory expenses is political. No politician in their right mind would suggest cutting Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid. No elected or appointed official cognizant of their fiduciary duties would suggest defaulting on interest payments for the national debt. Consequently, mandatory programs tend to become permanent fixtures in the annual United States government budget; they form figurative “third rail” issues, much to hot for any elected official to confront. This fact doesn’t change regardless of which party controls the presidency or congress; nobody is going to alter mandatory programs unless they increase their costs as a populist appeal to the electorate.

The political reality of the United States is that once a mandatory program is set in place, it is a permanent, ever-increasing part of the annual federal budget. The implication of this reality is that if the mandatory items grow in size faster than the overall budget, then the discretionary portions of the budget must shrink as they get squeezed out by the ever bigger boxes of expanding mandatory items.

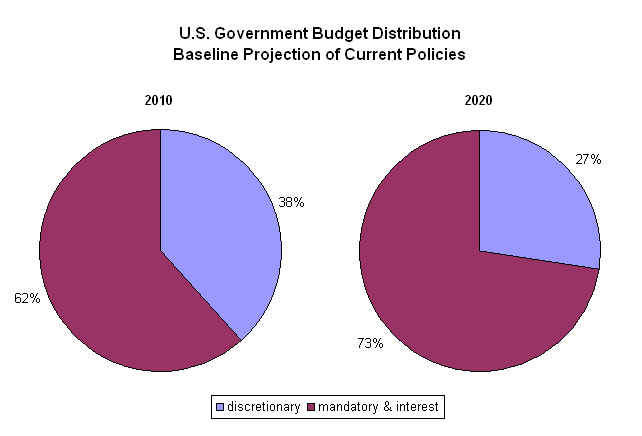

(click image for larger size)

Under current policies, mandatory and interest spending will grow from 62 percent of the budget to 73 percent of the budget in the next ten years.

That growth in mandatory and interest spending means that unless the budget grows significantly, which implies increasing our national debt even more significantly, everything that is discretionary spending must shrink by 11 percent. That means everything from alternative energy development to education to disease control to national defense must shrink by at least 11 percent during the next ten years.

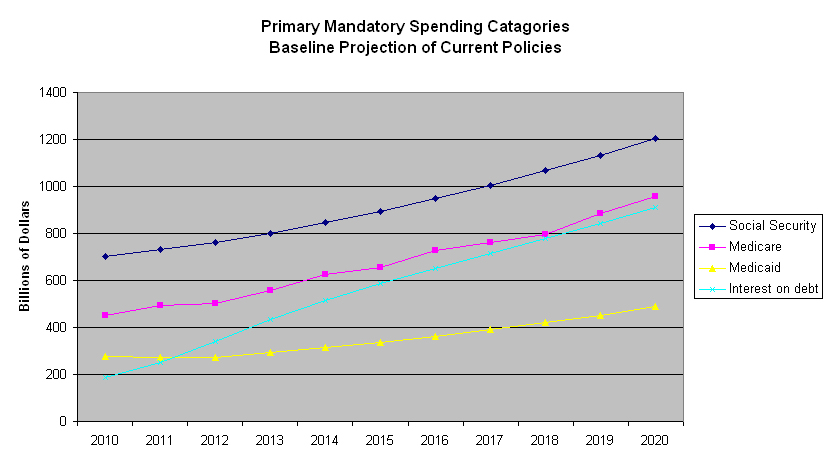

In the case of the United States, the primary ever bigger boxes for the foreseeable future are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid and interest payments on the national debt. Under current policies, by 2020 these four categories will grow by 34 percent.

(click image for larger size)

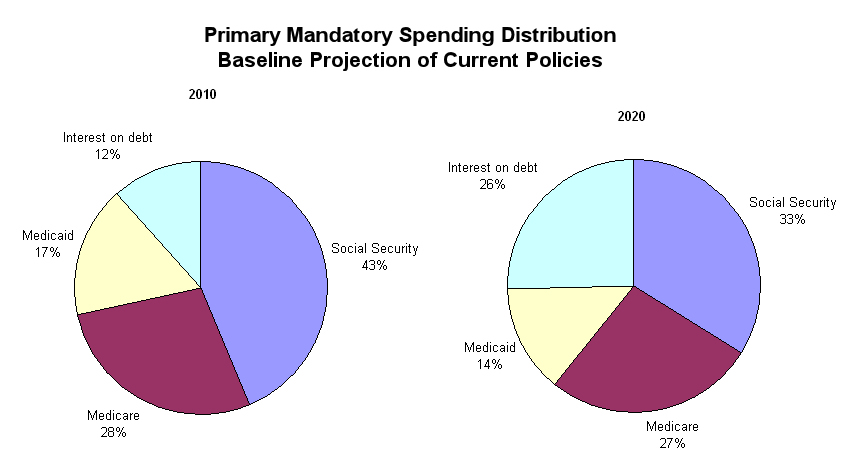

Of the four primary mandatory spending categories that will drive this expansion, interest payments on the national debt is the primary culprit. Over the next ten years, interest payments on the national debt will grow from 12 percent to 26 percent of the primary mandatory spending.

(click image for larger size)

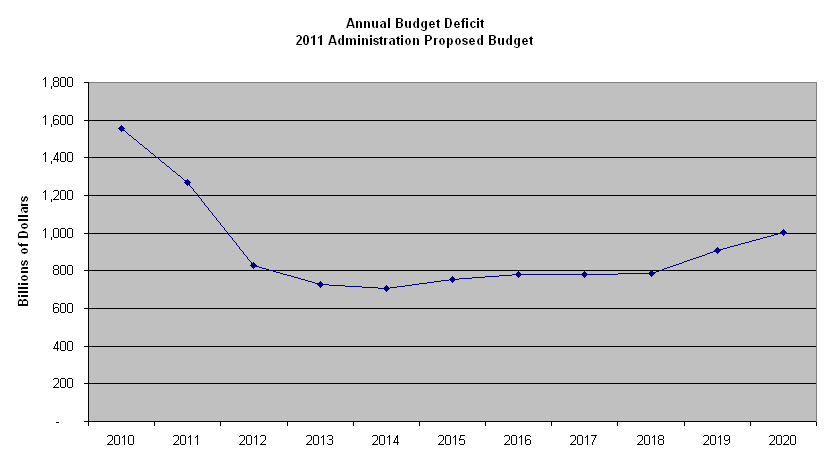

The reason the interest on the debt will grow so rapidly and to such large proportions is that there are currently no plans to decrease the national debt. In each of the next ten years the U.S. government is projected to continue to run an annual deficit, leading to an increase in the overall national debt.

(click image for larger size)

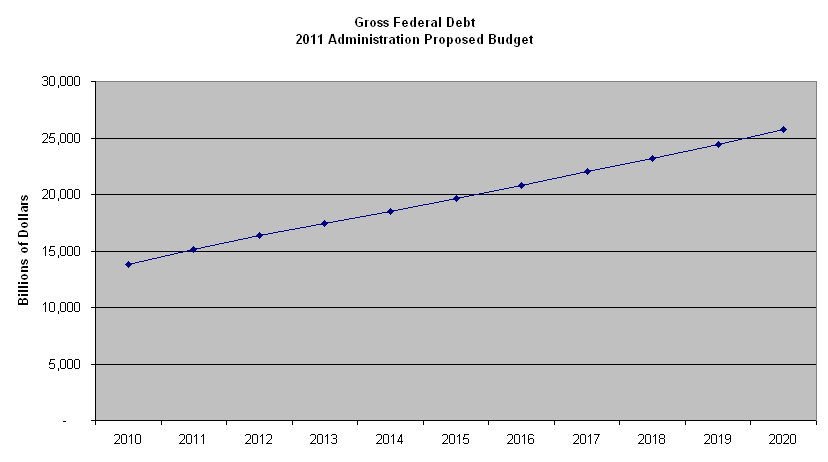

As a result of these ongoing deficits, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects the United States national debt will increase to a total of $25.76 trillion dollars by 2020.

(click image for larger size)

These future projections are troubling enough, but the really bad news is that they are almost certainly overly optimistic. The reason they are almost certainly optimistic is that they rely on assumptions that are very unlikely to be realized.

For instance, the administration and OMB assumptions include GDP growth rates from 4.4 to 6.0 percent, beginning with a 5.1 increase in 2011. They also assume continued low inflation rates ranging from 1.9 to 2.1 percent from 2011 until 2020. In addition, they assume historically low to moderate Treasury bill rates ranging from 1.6 to 4.1 for the decade.

A more realistic projection may be arrived at by considering that in the quantity theory of money, if higher money supply does not raise output it causes inflation, more colloquially expressed as inflation equals money supply times velocity. During the financial crisis unprecedented amounts of liquidity were added to the economy to stimulate activity. At that time, velocity was near zero and has remained sluggish. However, when velocity increases, it is questionable if available supply can be reduced fast enough to avoid high inflation rates. Once inflation ignites, it requires painfully high interest rates to tame.

Even shorter term, the costs for financing the national debt are likely to increase as interest rates rise from historic lows to more normal levels. Much of the additional liquidity pumped into the economy was financed with short term government debt. Because that debt was incurred when interest rates were very low, the cost to finance it was minimal. However, that short term debt is now coming due, $1.9 trillion dollars worth within this year alone, and since we don’t have the money to pay it off, the U.S. needs to roll it over into new, longer term debt. Longer term debt will require higher interest rates, reflective of historical norms. As a result, the U.S. will be refinancing $2.3 trillion of low cost debt into higher cost debt in the next two years. Along with that refinancing will come higher interest rates, thus, higher interest payments.

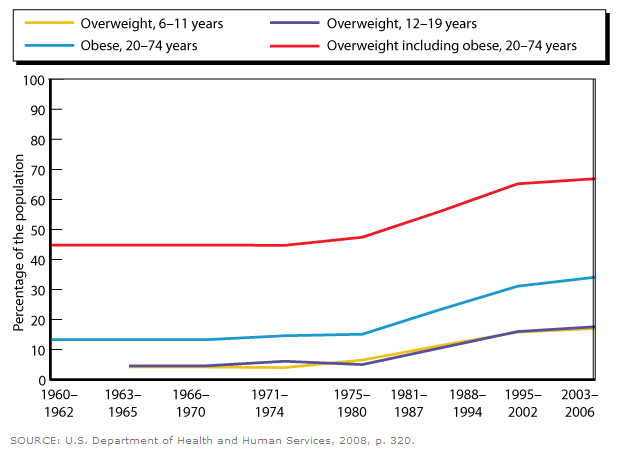

Aside from purely financial projections, the ticking time bombs of health care costs imbedded in Medicare and Medicaid often include best case assumptions. For instance, more than one third of adults in the United States are obese. Obesity nearly doubles the rates of debilitating, high cost chronic diseases and disability.

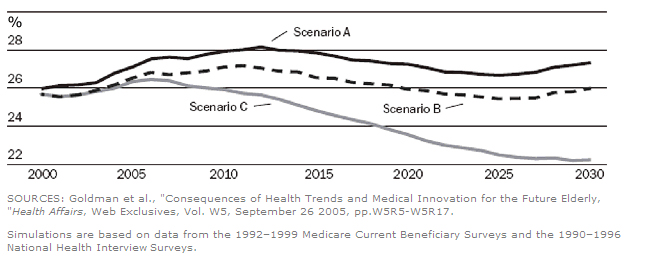

When measuring the long-term costs of health care, chronic disease states and disability are among the most significant cost drivers. When these conditions are projected forward, multiple scenarios are often used based on varying assumptions. For instance, when projecting rates of disability among the elderly, RAND notes that the estimated prevalence of disability among the elderly varies substantially depending on the assumptions made about the health of specific age groups.

In this example, in scenario A, they take into account the health and disability of younger populations and project the effects of these characteristics into the future; scenario B assumes that future Medicare beneficiaries resemble today’s; scenario C assumes that rates of disability will continue to decline among the elderly. It’s an easy guess as to which of these scenarios is likely to be used in an effort to present a rosy picture of future health care costs in the federal budget, when in reality, the spike in obesity among the U.S. population will increase rates of disability among the entire population, including the elderly.

(click image for larger size)

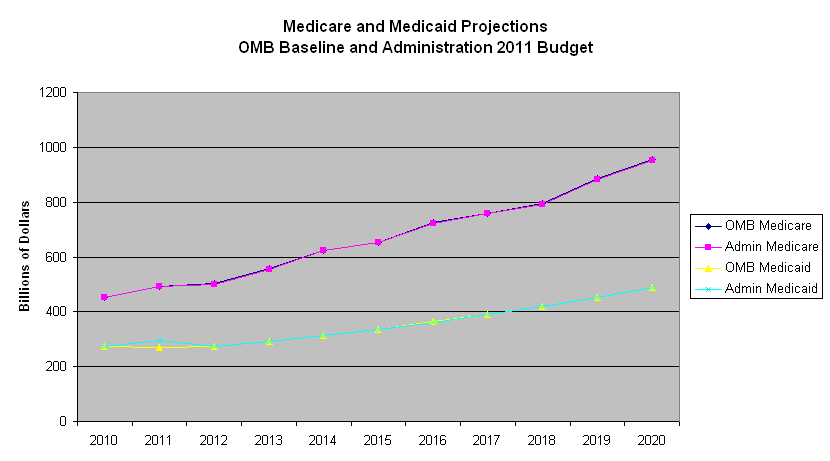

When evaluating government budget projections, it is very important to understand what scenario is used for assumptions of future costs. In this case, both the OMB’s baseline projections and the administration’s proposed 2011 budget projections make assumptions on health care costs that are more wishful thinking than reflective of the steep rise in obesity in the United States and the inevitable increase in society wide costs associated with that fact.

(click image for larger size)

Even under an optimistic scenario, in ten years mandatory and interest payment spending will consume 73 percent of the national budget, leaving 27 percent to pay for everything else the United States government provides, from defense to diaper standards. In ten years interest payments on the national debt will consume 26 percent of the primary mandatory spending. In ten years nearly 40 percent of the people in the United States will be obese, along with accompanying chronic diseases and disabilities and their associated high costs of health care. In ten years the United States will owe $25.76 trillion in national debt.

This is a near term threat. It is only ten years away. That’s not far enough into the future to let future generations worry about it. Essentially everyone reading this will be alive ten years from now and will be suffering the consequences if these challenges are not overcome.

All of this adds up to a looming, existential threat to this nation.

All we need now is a ruling class capable of addressing and overcoming the challenge coupled with nationwide sustainable political will to implement and sustain the solution.

I’m not holding my breath.

*******

Sources:

- United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

- Federal Reserve

- RAND

- New York University

- New York Times