Americans often have suspicions regarding their elected officials and money. Specifically, what are the politicians doing with all that money they are swimming in, and does any of that money stick to their fingers?

It’s difficult to not be suspicious when the 2008 elections rang in at a cost of $5.3 billion dollars. Candidates for the House of Representatives raised $1 billion dollars for the 2008 election, with the Senate candidates adding $500 million dollars. That’s more than $1.5 billion dollars to buy the seats of Congress.

The least expensive seat you could buy in Congress in 2008 went to Representative Marcia L Fudge (D-Ohio) who spent only $94,049 out of the $1,323,209 raised by the three contestants. The most expensive seat in 2008 was Minnesota’s senate seat, which cost $46,175,432, of which the winner, comedian Al Franken, spent $21,066,834.

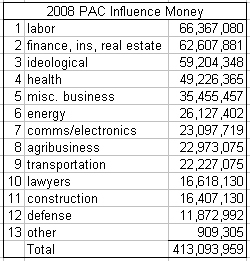

In 2008 the 14,446 lobbyists who permeate the United States political system spent $3.3 billion dollars influencing the government. In the same year, Political Action Committees (PAC) with foreign ties contributed $6,456,465 to candidates and domestic PACs threw in $413,093,959 to purchase access and shape public policy. In addition, the so called “527” groups, named for the section of the tax code that created the loophole they operate in, threw in $439,210,000, every dollar of which was completely unregulated by the Federal Election Commission and subject to no limits.

When Americans ponder these billions of dollars flowing into the government, dollars whose only purpose is to buy influence with the people tasked with creating the laws and policies of the country, it’s only natural to be concerned. When Americans compare the challenges the country faces to the lack of logical, pragmatic and timely action on the part of Congress, they grow frustrated, especially when they sense connections between the lack of action and the sources of the billions spent to influence the members of Congress. To then look at Congress and see a group of people whose average net worth ranges from more than $4 million dollars for the House and $12 million dollars for the Senate, it’s not a big leap for Americans to wonder if any of the billions of lobbying, PAC and 527 dollars are ending up in the pockets of Congress.

Why isn’t anything done on Capitol Hill about the challenges we face as a nation? What does all that money buy? And where does all that money end up? Those are natural questions.

Why isn’t anything done?

For the cause of the lack of action addressing the major challenges that face the country, you needn’t look much further than the PAC money that goes directly to members of Congress.

Note: The ideological category includes all the single-issue and partisan money that is used to decrease cooperation and increase division and gridlock. With the recent Supreme Court decision to allow unlimited influence payments by corporations and unions, that situation is destined to severely worsen.

PAC money is invested in members of Congress to ensure that a particular group’s interests are protected. That means that meaningful change on any of the major challenges facing the nation is essentially impossible. Banking and finance system reform? Not likely when there’s more than $62 million to extend the status quo. Health care reform? Not a chance with more than $100 million of health industry and ideological money to purchase gridlock. Energy independence? Good luck on that when the energy industry can buy their Representative or Senator of choice with a portion of the $26 million they spent purchasing influence in 2008. And remember, this is just the PAC money; to fully understand why nothing ever happens in Washington, you’ve got to include the $3.7 billion in lobbyist and 527 money flooding the corridors of power.

What does all that money buy?

The second question, “What does all that money buy?” is simple too. It buys whatever the purchaser wants. Want a special tax break for your market? How about a federal contract including specifications that only your product or company can meet? How about special terms or benefits in legislation for your union? It’s all available—for a price.

Recognize any of these names?

Source: Center for Responsive Politics www.opensecrets.org

Note: The American Association for Justice is the rebranded Association of Trial Lawyers of America (ATLA)

Those are the top 50 purchasers of influence in Washington over the last 20 years. The next time you wonder why change doesn’t ever seem to happen in Washington, but some industries, companies and unions always seem to come out OK, check this list for stakeholders.

But how do those stakeholders get a return for all the money they invest in purchasing influence in Congress? One popular way for Congress to dole out repayment for all the billions of dollars invested in influence payments is through earmarks. Earmarks are additions to legislation for specific funding to specific individuals, organizations or companies or that exempts those same individuals, organizations or companies from taxes, duties or fees.

In 2008, the United States Congress enacted 43,524 earmarks for a total of $2,657,220,000.

In addition, the Congress made countless new laws and changes to the collection of regulations affecting every business, organization, union, city, community, farm, man, woman and child in this country. Every one of those laws and regulations was written not by our elected Representatives and Senators, but by their staff members and lobbyists, many of whom trade places on a regular basis. Consequently, those laws and regulations are not a product of what is best for the country or what the country needs to overcome the myriad of challenges we face. Instead, those laws and regulations are what is best for the people paying billions to purchase influence on Capitol Hill.

That is what all the money buys—what is best for the people paying billions to purchase influence on Capitol Hill.

Where does all that money end up?

As any tin pot dictator or drug lord can tell you, billions of dollars have to go somewhere. With all the billions of dollars spent on purchasing influence in Washington, D.C., it’s natural to wonder where it ends up.

Americans’ suspicions are aroused when they learn of politicians such as Bobby Jindal, who worked for one year out of college in 1995 and then spent the rest of his career in politics earning modest salaries. When Jindal left the U.S. Congress in 2007, 12 years later, he was debt free and worth more than $2.5 million dollars.

So where does all that money end up? Does any of it stick to the fingers and line the pockets of the members of Congress? That question is difficult to answer precisely because the financial reporting requirements for members of Congress are very loose, and allow wide ranges in reporting categories. Ranges are as much as $25 million dollars as well as one top category of $50 million or more. Thus, it is impossible to know if a particular asset held by a member of Congress is worth $25 million or $49 million, or $50 million or $500 million. In addition, it is extremely easy for members of Congress to hide assets with spouses, family members or structures such as trusts that are exempt from reporting requirements. Nonetheless, it is possible to get a reasonable picture of the net worth of members of Congress.

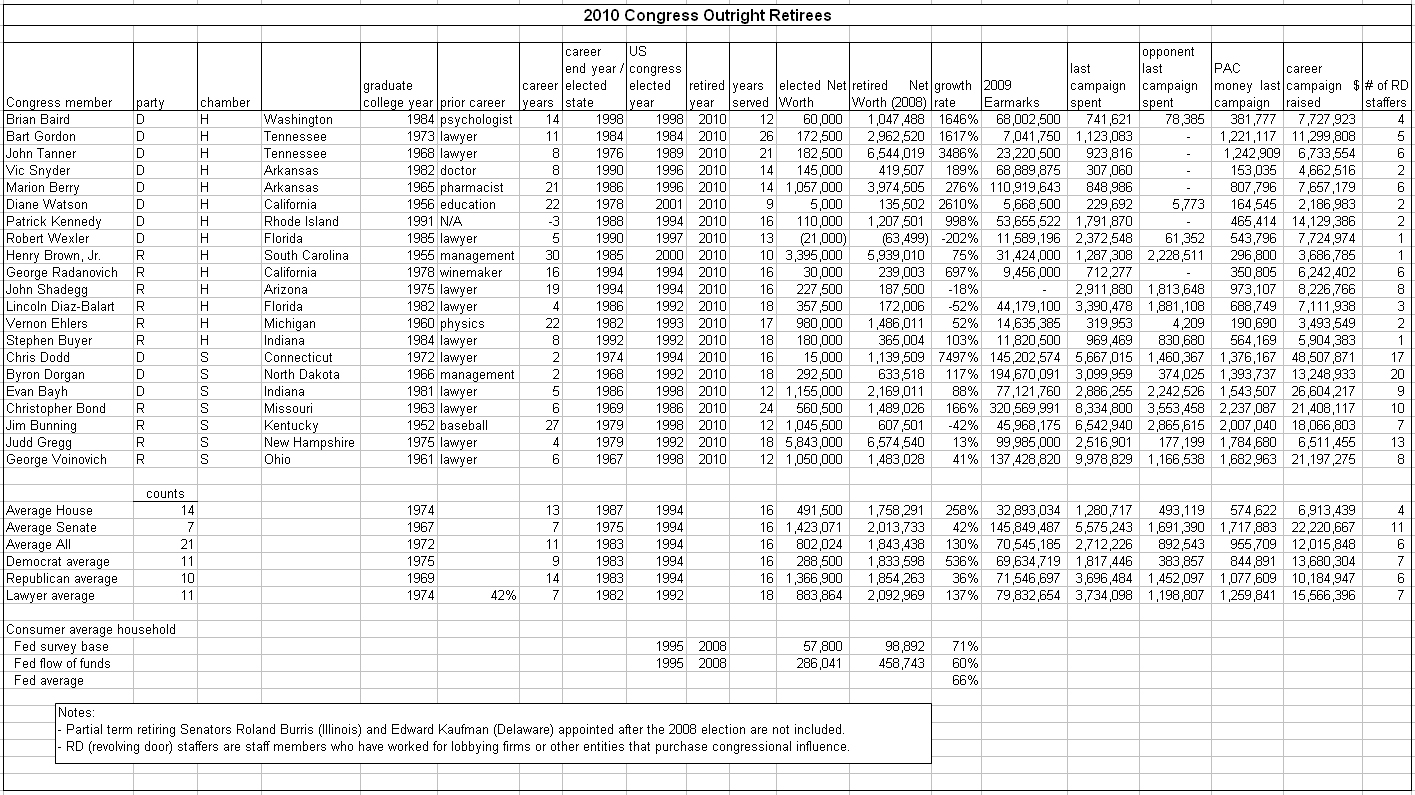

To determine if any of the billions of dollars used to purchase their influence sticks to them, I analyzed the current group of Representatives and Senators who are retiring outright in 2010, meaning they are not seeking any further political office.

(click for larger image)

The analysis reflects that the retirees’ average tenure in Congress was 16 years, from 1994 to 2010. More than two thirds, 67 percent, of these elected officials had higher growth in their net worth than the average American citizen during that period.

Some members of Congress showed remarkable, even astounding, growth in their wealth, such as Chris Dodd, whose net worth increased 7,497%, from $15,000 to $1,139,509, in only 16 years. He achieved that amazing feat while maintaining a home back in Connecticut and a residence in Washington, D.C., one of the most expensive cities in the world. And he accomplished all of this on his relatively modest government salary.

Another noteworthy member is John Tanner of Tennessee, who in 21 years achieved 3,486% growth in his net worth, from $182,500 to $6,544,019, again while maintaining two homes and on a relatively modest government salary.

And while there are members who never could figure out how to manage money, such as Robert Wexler of Florida, who entered the House deep in credit card debt and left the same way, all more common are members such as Brian Baird, who turned $60,000 into $1,047,488 in 12 short years.

Those three Congressmen, Dodd, Tanner and Baird, accounted for $236,425,574 in earmarks in 2009. Together, they raised $62,969,348 in direct payments during their careers, not including lobbying, PAC and 527 money. They turned a starting collective net worth of $257,500 into $8,731,015 on modest government salaries each while maintaining two homes, one in a very high cost city.

Where does all the money go? Does any of it stick?

You be the judge.

Regardless of how much or how little of the billions of dollars spent in Washington to buy influence sticks to the fingers of Representatives and Senators, one thing is certain: the United States and what is best for the country’s short- and long-term future is not the top priority of our elected representatives. Money is.

In 2008, PACs, lobbyists, 527s and others spent $21,066,834 to buy a comedian a Senate seat. Obviously, under the current system, the joke is on us.

*******

Sources:

- Data provided by Center for Responsive Politics opensecrets.org http://www.opensecrets.org/index.php

- Web sites of Senators and Representatives included in this analysis

- The Federal Reserve Board

- United States Census Bureau

- Office of Management and Budget

- Washington Post

- Wall Street Journal

- Wikipedia