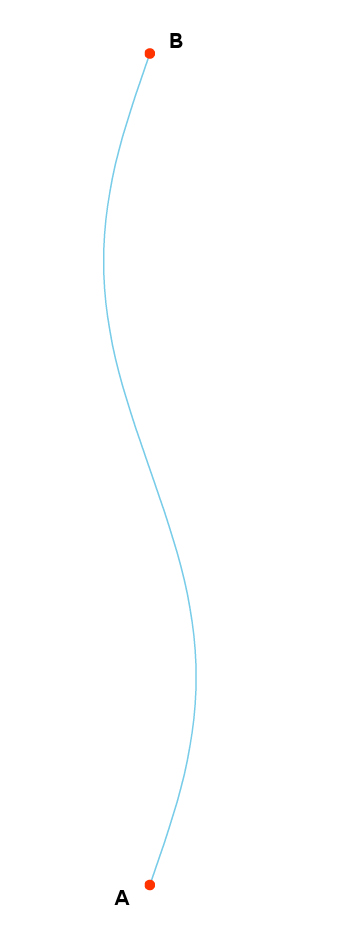

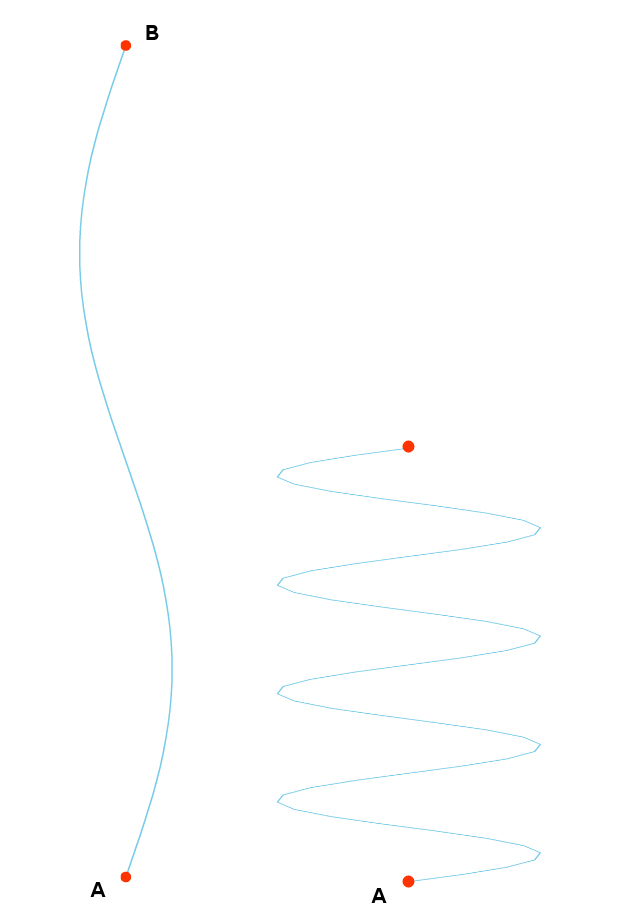

As any school kid can tell you, the quickest way to get from point A to point B is a straight line.

However, life doesn’t usually work in straight lines, and just like driving a car, getting anything from A to B is usually a long series of slight corrections: a little right, a little left, repeat.

In doing so, you get from A to B with a minimum of time and effort.

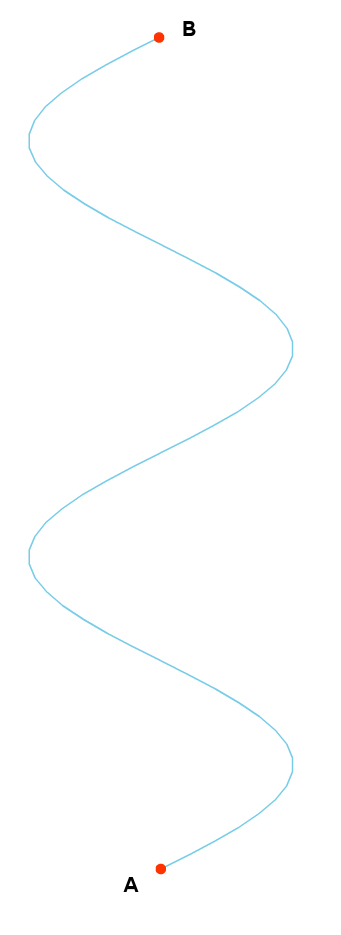

If you make bigger changes of direction along the way, you can still get to point B, but the repeated changes in direction add distance to the journey, so you must travel much further and it takes more time and energy to arrive at the goal.

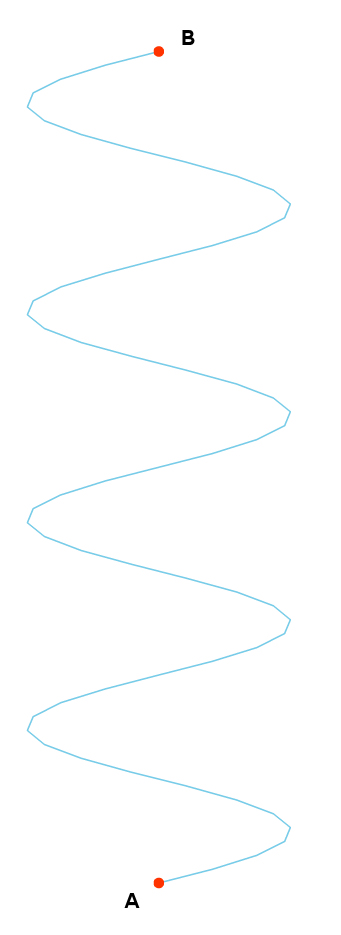

If you make repeated abrupt changes in direction you spend most of your time alternating between right and left, with very little energy invested in actually moving towards your goal.

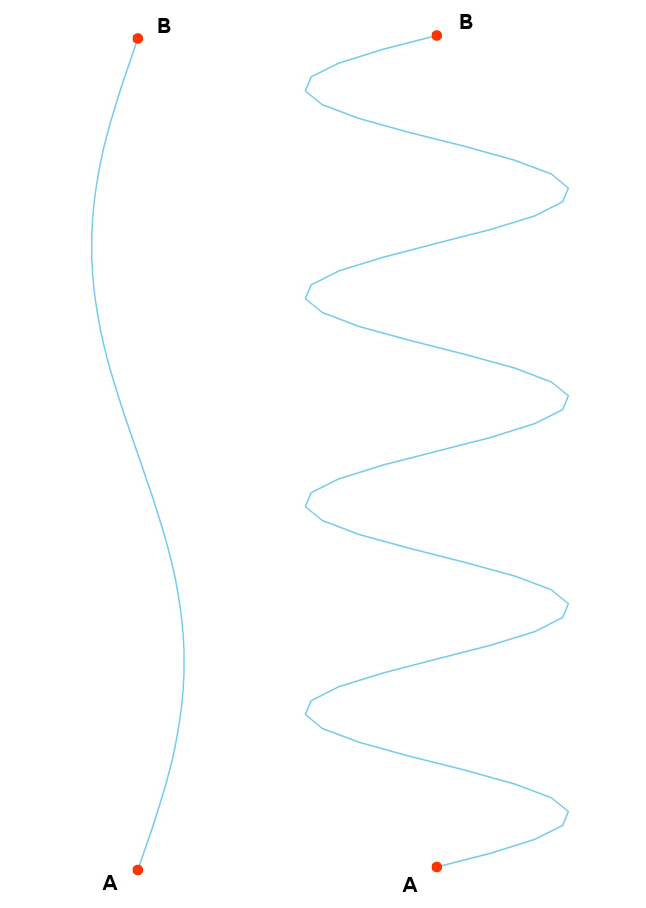

When you compare the two methods, gentle mild corrections right to left with severe vacillation between extremes, it’s easy to see which way is more efficient.

But that image is misleading, because it implies that both methods yield the same results in the end. Actually, alternating between extreme right and extreme left will never get you to the same goal. You spend so much time and energy going back and forth that the clock hits zero, you run out of energy and everyone else operating more efficiently simply passes you by. You never get to point B.

And that, simply put, is what has happened to government in the United States of America.

Historically, the two major parties stayed on a fairly moderate course, alternating between center right and center left, but always finding a way to move the country forward, getting us from point A to point B.

However, in the last few decades, and especially the last decade, the parties have moved steadily toward the extreme ends of the political spectrum. As they’ve spent more time swinging the country wildly from far right to far left and back again, we’ve made less and less progress forward until now governance is at a standstill, in total gridlock. Point B remains far over the horizon, while other nations, operating within moderate political parameters, steadily pass us by.

How did this happen? How did we move from a position of “can-do” global political leadership to stuck-in-the-extremist-mud also ran?

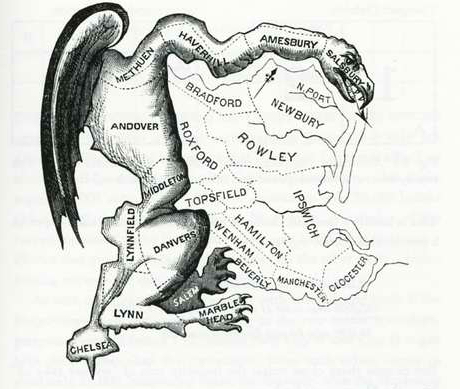

It all began with a mythical creature discovered in 1812. That year, Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry redrew the boundaries of the districts used to elect the state legislature to favor his Democratic-Republican party over the opposing Federalists. Governor Gerry’s goal was to create districts that would guarantee his party victory and cripple the opposition. To accomplish that goal he created a bizarre electoral district by connecting otherwise disparate and unassociated areas of Essex County.

The Boston Gazette opined that the elongated district created by Governor Gerry resembled a salamander. The editor of the Boston Weekly Messenger responded, “Salamander? Call it a Gerrymander!” Weekly Messenger cartoonist Elkanah Tisdale took the concept and produced the first known illustration of the now-famous political animal, the Gerrymander.

Since 1812, the word gerrymander has been used to describe the process of creating distorted electoral districts to ensure that the controlling political party faced no effective opposition.

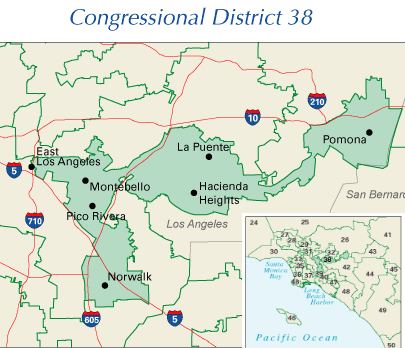

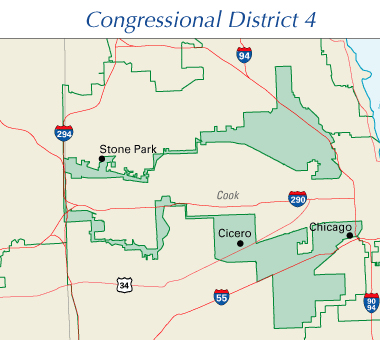

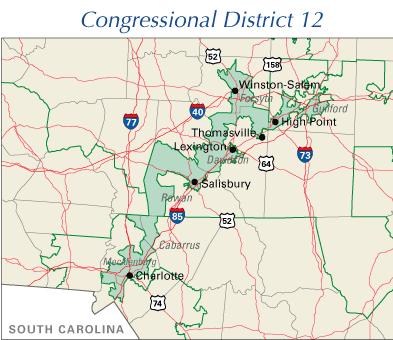

The practice lives on today, as these examples show:

Why are gerrymandered districts so bad? Gerrymandered districts create short term issues and long term trends that destroy the prerequisites of representative democracy. Here’s how.

Short term, gerrymandered districts create “safe” seats for a political party. “Safe” seats mean that within a gerrymandered district, the candidate of the favored party will always win. In an American gerrymandered district, an election is exactly the same as an election in Putin’s Russia, the Communist party’s China, or Chávez’s Venezuela. The chosen candidate is going to win. Period.

Longer term, gerrymandered districts inevitably drive political parties toward ideological extremism. This is due to the lack of contested general elections between the parties, causing the “winning” candidates to be chosen in the primary election.

Candidates for the general election held in November are selected in a primary election held earlier the same year, typically in late winter or early spring. When a party knows that their candidate can never be defeated in a general election, the primary election becomes the de-facto contest to determine the winner for that district.

Very few voters turn out at the polls for primary elections, especially in non-presidential election years. For instance, in 2008, a presidential election year, when primary election turnout is at its highest, an average of 31 percent of eligible voters turned out for the nation’s primaries compared with more than 63 percent for the general elections later that same year. In non-presidential election years, it is not uncommon to have fewer than 20 percent of eligible voters participate in a primary election.

The voters who do participate regularly in primary elections are mostly party activists, hard-line extremists and ideologues. Very few moderates show up to vote in primary elections.

What this adds up to is that a candidate who wants to win the primary election must appeal to, if not pander to, those same party activists, hard-line extremists and ideologues. A moderate candidate has essentially no chance to win a primary against a radical candidate who espouses the views of the party activists, hard-line extremists and ideologues who dominate voting in primary elections.

In a gerrymandered district, there is no competition in the general election. It’s just like Russia, China and Venezuela, the winning party has already been determined. In a gerrymandered district, the only competition is in the primary election. In the primary election, the only candidates who can win are those who appeal to party activists, hard-line extremists and ideologues. The more hard-line extremists and ideologues are elected, the less compromise is possible and the more gridlock seizes the government.

The bad news is that more and more districts in the United States are gerrymandered or “safe.” Since 2000 the number of contested seats, meaning those not gerrymandered or “safe,” in the House of Representatives has dropped from 154 to 104, a reduction of 53 percent. In the 2010 election, 331 of the 435 House seats, 76 percent, are considered “safe” or gerrymandered. Considering what happens in “safe” or gerrymandered district primary elections, 331 hard-line extremists and ideologues are likely to be elected to the House in 2010.

Given those numbers, is it any wonder we should expect yet another violent turn of the wheel, yet another radical change in direction, yet another tangential path perpendicular to where point B lies? Given those numbers, is it any wonder we should expect more entrenched ideologues? Given those numbers, is it any wonder we should expect more non-functioning government?

The current state of government in the United States is rancor, dispute, bitter partisanship and gridlock. Even the participants and long time observers feel that way, as reflected in these quotes:

“I’ve been around Washington for 40 years, immersed in the politics of Congress and the White House. And it’s nasty and brutish, as much or more as I’ve ever seen.” – Norman Ornstein, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute

“This past year was – by several measures — the most partisan ever — or at least since Congressional Quarterly began taking stock in 1953.” – National Public Radio

“The problem is the combination of highly ideologically polarizing political parties…” – Thomas Mann, congressional scholar at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution

“Challenges of historic import threaten America’s future. Action on the deficit, economy, energy, health care and much more is imperative, yet our legislative institutions fail to act. … There are many causes for the dysfunction: strident partisanship, unyielding ideology, a corrosive system of campaign financing, gerrymandering of House districts, endless filibusters, holds on executive appointees in the Senate, dwindling social interaction between senators of opposing parties and a caucus system that promotes party unity at the expense of bipartisan consensus.” – moderate Senator Evan Bayh (Democrat, Indiana), in an editorial regarding his resignation from the Senate

“They insist on moving to the left or moving to the right, and I think you’re seeing over the years the moderates have disappeared and continue to disappear.” – Former Senator William Cohen (Republican, Maine)

“If you’re on either fringe of the party, you have an easier time raising money.” – Senator Arlen Specter (Democrat, Pennsylvania)

“Moderates are going the way of the dinosaur.” – Darrell West, vice president and director of governance studies at the Brookings Institution

“What it means is the most partisan elements of our society, those on the left and right who believe their party is right and the other guy is always wrong, are electing, to the best of our count, almost 350 members of the 435 members here in the House. People are responsive to the people that elect them, so you have the left and the right here, and there’s very little in the middle.” – Representative John Tanner (Democrat, Tennessee)

“80 [percent] of the members come from districts where their race is their primary, it’s not the general election. They don’t get rewarded for compromising; they get punished if they compromise with the other side.” – Representative Tom Davis (Republican, Virginia)

“And to use the politics of fear and division and hate on each other — we are at a point right now where it doesn’t make a damn whether you’re a Democrat or a Republican if you’ve forgotten you’re an American.” – former Senator Alan Simpson (Republican, Wyoming)

“I used to think it would take a global financial crisis to get both parties to the table, but we just had one. These days I wonder if this country is even governable.” – G. William Hoagland, fiscal policy adviser to Senate Republican leaders

Almost nine out of every ten Americans, 86 percent, believe the government of the United States is broken.

Electing more hard-line extremists and ideologues in rigged elections perpetuates the brokenness and makes us no different than voters in rigged elections in Russia, China and Venezuela.

Electing more hard-line extremists and ideologues ensures nothing more than yet more violent swings from right to left and back again.

Electing more hard-line extremists and ideologues does not advance us from point A to point B; it does not advance us forward.

It just puts us further behind.

*******

“In 2001, John Zogby, the pollster, told our Republican caucus, ‘There is a burgeoning centrist third party waiting to be formed.’ Either party could make a strategic decision to capture the center, he said, or both could wait for a third party to fill the vacuum.” – former Senator Lincoln Chafee (served as a Republican, Rhode Island, currently Independent)

*******

Sources:

- George Mason University

- Congressional Quarterly

- Merriam-Webster

- Wikipedia

- Wikipedia Commons

- The Cook Political Report

- National Public Radio

- New York Times

- CBS News Polls

- CNN/Opinion Research Corp.

- CNN

- Designorati

- Gwycon.com

Nicely written, I work in the 12th in NC and we are very slow to see any change here. Who said third world politics need to stay off shore, we import everything else. The best advice is to vote early and vote often.

Jack

I’ve taken Jack’s advice but it didn’t work. I lost track of the votes I cast for Norm Coleman and Al Franken still won.

Always remember: two wrongs do not make a right, but three rights make a left.